“Mnemosyne, one must admit, has shown herself to be a very careless girl.”

Vladimir Nabokov, Speak, Memory

July 2017. During a research trip to special collections at the University of Edinburgh (thank you, Bibliographic Society of America!), I came across a small miracle: an extraordinary little book arrived when I asked to see The Indian Primer, a seventeenth-century reading manual used to teach converted Native Americans how to read and write printed on the first colonial press at Harvard college. The tiny volume, only 2.4 by 3 inches large and barely the size of the palm of my hand, was bound in crisp white leather artfully emblazoned with foliated designs and large plum strawberries at the center of its deliciously delicate front and back covers.

I knew right away this was no ordinary binding. Usually, utilitarian leather covers of the period came in a saturated chocolate brown and were free of expensive ornaments. What story was lurking in this pale little gorgeousness?

A first clue, I suspected, hid in the binding’s leafy ornaments, difficult to recognize because they had turned like the strawberry an undifferentiated muddy brown. Natural pigments are very light sensitive and have a much shorter shelf life than synthetic colorants, which is why I started wondering, might the binding have a Native American background? The missionary origin and explicit Indigenous readership of the Primer made Native craftsmanship a possibility.

The only problem, of course, was how I could prove this exciting hypothesis? A gift from a Scottish donor in the seventeenth century, the book has a thin catalogue entry and no record survives of the artist who created the binding. This absence is not surprising. Bookbinders frequently go unrecorded, and Western archives tend to erase Native American voices, perspectives, and knowledge. Memory, as Nabokov painfully puts it, is indeed a very careless girl.

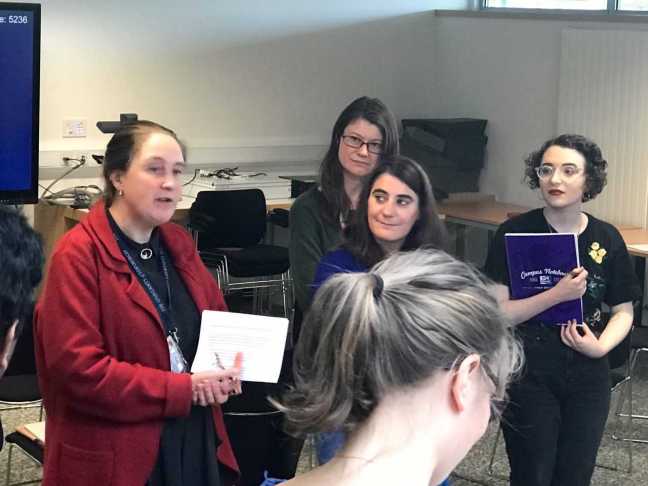

October 2018. I am back at Edinburgh and in special collections. This time, however, I am working on proofs of my hypothesis. I am in the company of a cross-disciplinary group of scientists from different universities: chemists, archeologists, librarians, and biologists, who have been working all year to solve the riddle of the binding. I invited them to meet for the first time in the flesh at the workshop “Biologies and Ethnographies of the Book” (thank you, Center for the History of the Book!). All of them have developed nifty new analytic technologies that make materialities speak.

Some gingerly send laser light onto silent colored surfaces to identify the pigments originally used. Others gently rub leather surfaces with an eraser, collect tiny rubber splinters (and enclosed even tinier leather particles), analyze the crumbs, and identify the animal species skinned for their precious hides. Memory might be careless but it leaves traces in the most unlikely places.

Even if the archive is silent, the materialities of the binding hold rich narratives. They remember what we have forgotten or wanted to forget. The process of recovery is ongoing and certainly challenging. So far, all aspects of the binding studied test positive for American provenance.

Speak, materialties!

— Steffi Dippold, Assistant Professor