Talking about Midwestern history, the conversation often turns as flat as many perceive the Great Plains to be. History buffs may know Bleeding Kansas or Brown v. Board of Education, both significant moments in the fight for African American civil rights.

However, frequently overlooked in both academic and public awareness are Mexican American histories central to our regional past. Lack of second language requirements in most of our schools makes sure those hidden histories remain forgotten and inaccessible to English-only language readers.

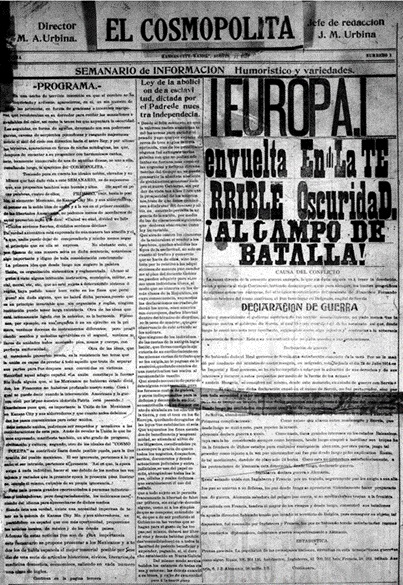

One stunningly rich if forgotten local Latino voice is the first Midwestern Spanish-language newspaper El Cosmopolita, printed in the now popular neighborhood of Westside, Kansas City, Missouri. Hardly any paper trail has survived about the authors and editors of the paper save for the newspaper itself.

During this summer and thanks to a McNair fellowship, I had the opportunity to research in local archives and attentively explore El Cosmopolita as a first step in recovering this vital document for further scholarly discussion.

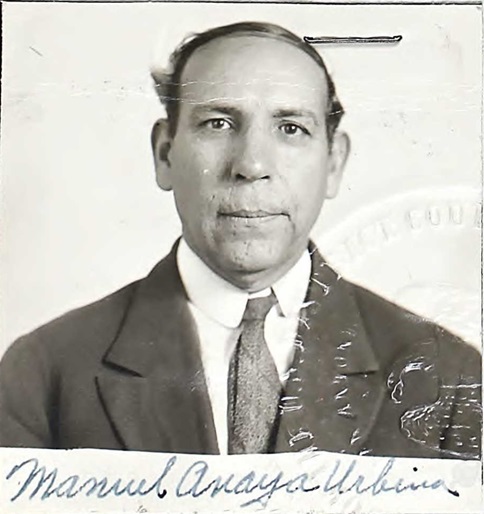

Two Mexican immigrant brothers, Manuel Anaya and Juan Manuel Urbina, founded El Cosmopolita in the early twentieth century to support local Mexican communities and their rights.

Manuel Anaya Urbina, co-founder of El Cosmopolita

Manuel Urbina, a Baptist minister and teacher, centered his advocacy on self-improvement, which the newspaper promoted tirelessly, announcing in one article that there would be “in each issue an English class” (Urbina & Urbina 1).

Juan Urbina, in contrast, worked as a manual laborer and experienced first-hand the discrimination and exploitation Mexican laborers faced in local industries, including railroad maintenance, sugar-beet farms, and meat-packing plants (Chelan). His perspective would have mostly closely aligned with the local Mexican labor union for which El Cosmopolita served as a mouthpiece.

The union la Union Mexicana Benito Juárez featured in many of El Cosmopolita’s issues. Both Urbina brothers were active union members and it was apparent in their writing — the very first issue of El Cosmopolita advocates for the unification of “all that is possibly Mexican in Kansas City, Mo. And its surroundings.”

Additionally, the newspaper reported on union sessions, speeches from the president, and printed meeting times for la Union Mexicana Benito Juárez. The agenda of the forgotten labor union and its connection to El Cosmopolita can be deduced from the shared values of its namesake, Benito Juárez, and the Urbina brothers. Benito Juárez was a notorious former president of Mexico and the first Indigenous person to hold the office. His steadfast resistance and his celebration for Mexican nationalism and pride were central to both the union and El Cosmopolita (Scholes). Though no scholarly article or local archival record exists that explores la Union Mexicana Benito Juárez, El Cosmopolita held a megaphone to the labor union’s activities and goals.

On the printed pages, El Cosmopolita featured stylish art deco fonts and attracted the reader’s attention to articles through clever titles and ironic wordplay. Divided into six columns per page, the front-page often extended important essays across multiple sections. For example, El Cosmopolita dedicates three columns on the far right to the announcement of World War I, declaring “EUROPE. Shrouded in Terrible Darkness on the Battlefield!” (Urbina & Urbina 1). The announcement outdated the actual outbreak of the war by about a month, given that World War I started in July 1914, one month before the first issue of El Cosmopolita was published. Yet, the delay is an important reminder of the isolation Mexican immigrant communities experienced in the Midwest. To provide timely news to Spanish-speaking readership was therefore a key ambition of El Cosmopolita.

My favorite essay from El Cosmopolita is the “Programa,” in which the Urbina brothers defined the purpose and intellectual tradition of their newspaper. The article ran in the left-hand side of the first issue, marking the importance of this origin narrative. The “Programa” opens with references to Indigenous Mexican deities and celebrates them as ancestors and founding principles. One reference addresses Itzpapalotl, an Aztec goddess central to Mexican culture associated with rebirth and a distinct butterfly symbolism that organizes the larger argument of the “Programa” (Mursell).

Drawing of Itzpapalotl from the Codex Borgia.

Researching the newspaper and its arguments was lots of fun given the multilayered, tongue-in-cheek prose, and deeply poetic narrative of many articles.

Yet, much more work remains to be done in order to recover the full intellectual range and political interventions of this important newspaper and print culture archive that records an understudied diverse cultural history of our region.

Works Cited

Codex Borgia, pg. 66, ca. 1250-1521. Foundation for the Advancement of Mesoamerican Studies. Accessed July 24, 2023. http://www.famsi.org/research/loubat/Borgia/thumbs4.html.

David, Chelan. “Kansas City Latino History and Culture.” The International Relations Council. Accessed July 21, 2023. https://www.irckc.org/kansas-city-latino-history-and-culture/.

Mursell, Ian. “Itzpapalotl and her Chichimec Origins.” Mexicolore. Accessed July 21, 2023. https://www.mexicolore.co.uk/aztecs/ask-us/can-you-tell-me-more-about-Itzpapalotl-and-her-chichimec-origins.

Scholes, Walter V. “Benito Juárez, president of Mexico.” Britannica. Updated March 17, 2023. https://www.britannica.com/biography/Benito-Juarez.

Urbina, Manuel Anaya and Juan Manuel Urbina. El Cosmopolita, Issue 1 (Kansas City, Missouri), 1914-1919. Missouri Valley Special Collections.

— Liberty Belote (BA ’24)