Today we share the third of six pieces of public writing selected for publication from an assignment in ENGL 801 “Graduate Studies in English”: a piece of public scholarship (700-1,000 words) which tailors an academic paper and its scholarly intervention of 10-12 pages for a general-interest audience.

Read more about the assignment and the first publication, “Mina Harker is More Than Just a Love Interest” by Destiny Munns (MA ’25), in the post from December 7, and the second publication, “Resting in Peace: Why Once Upon a Time in Hollywood Keeps Sharon Tate Away from the Action” by Mike McCoy (MA ’25), in the post from December 11. Now, on to “What Happens to Childless Mothers” by Beth Jones (MA ’25) —

— Karin Westman, Professor and Department Head / Instructor for ENGL 801 ZA (Fall 2023)

Each year, 50,000 children die in the United States and leave behind childless parents (Roche, 2020). While many adults experiencing grief continue to identify as parents, not all of them do.

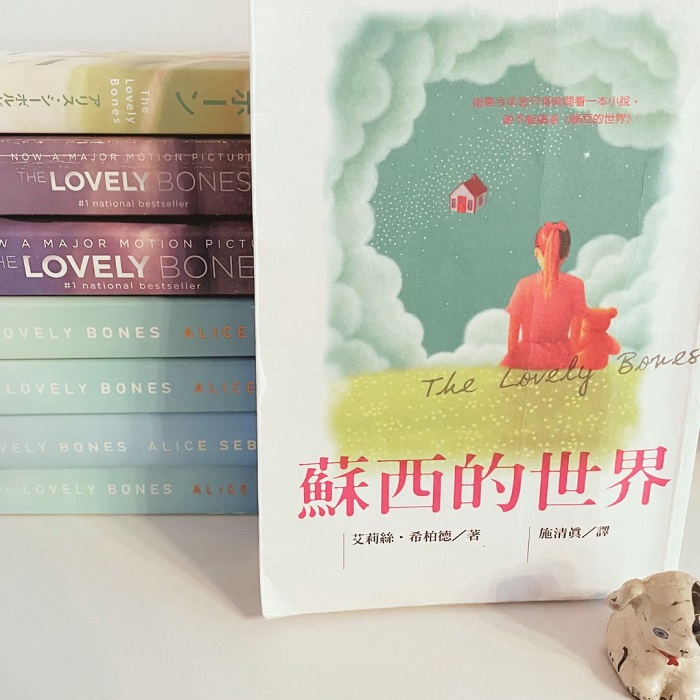

In the case of Abigail Salmon in Alice Sebold’s 2002 novel The Lovely Bones, motherhood is something that ends for her when her child passes away.

Here’s why.

Abigail Salmon doesn’t plan on losing herself to motherhood, but through a combination of societal pressures, conflated family obligations, and a desire to be a “good” parent, she loses sight of her personal goals and emotionally throws herself into raising three children. When Susie, her oldest daughter, passes away at the beginning of The Lovely Bones, Abigail’s life is thrown into chaos. Readers are offered a glimpse into Susie’s experiences in the afterlife, but it’s Abigail Salmon’s reaction to losing her child that speaks volumes as to what her true opinions on motherhood are — and how the restrictive desire to be a “perfect” mother devours her own sense of self-worth and identity.

Sebold paints a world in which Susie is able to exist as a literal ghost, but her mother feels like one.

Prior to Susie’s passing, Abigail Salmon always made her children dinner (Sebold 10), knit them matching winter caps (19), and was wondering why Susie was late for supper on the night she was killed (10). Sebold certainly captures both the monotonous and ritualistic nature of motherly duties. Before Susie’s death, Abigail performs these tasks with love and care, but life after Susie is a slow descent into isolation and withdrawal for Abigail. After Susie dies, she no longer needs to perform these duties. Knitting caps was something Abigail did for her oldest child. No one else. Now that Susie is gone, Abigail decides not to partake in these performative tasks.

Abigail’s grieving is closely entangled with her return to her identity as an individual person and not “just” a mother. The idea of Abigail’s secret identity as a woman is something the other characters in the book, including Jack Salmon, struggle with. They have strong ideas as to how Abigail “should” grieve, none of which include seeking her own personal ideas, endeavors, or activities. Psychology scholar Laura J. Cammaroto argues in her thesis, “Unexpected: Identity Transformation of Postpartum Women,” that many women who become mothers struggle with the loss of their previous role as an individual. She explains, “Those beliefs, or self-imposed expectations, have to be reevaluated considering the new information and responsibilities” (8). Cammaroto continues on to address the idea that when an individual adult becomes a mother, they are forced to reconcile their independent nature with their new maternal obligations. In Abigail’s case, her dreams are forever put on the back burner of her life, destined to be forgotten. Then Susie vanishes, and suddenly, Abigail finds a glimpse of freedom. She remembers that she used to be her own person, and she wonders if she can find that self-satisfaction — and that solitude — again.

The idea that a mother may feel weighted down by the existence of her children or the responsibilities they present is not a new concept, and while readers may be shocked at Abigail’s seemingly callous reaction to her child’s death, Dawn Marie Dow explores this common concept in her book, “Integrated Motherhood: Beyond Hegemonic Ideologies of Motherhood,” and explains that this reaction is normal. Dow notes, “Sociologists have identified a consistent set of hegemonic ideologies that influence women’s work and family decisions” (180). When a woman becomes a mother, she is provided with a list of tasks she must complete, many of which include setting her own desires aside so she can “do what’s right” for her children. This list may include realistic and important duties such as driving the child to appointments or making sure they have a healthy diet; however, sometimes the duties assigned to a mother may feel overwhelming and all-encompassing.

Once readers start paying attention to Abigail Salmon, they’re offered yet another set of questions: “How happy was Abigail Salmon before her child died?” and “Did she even want to be a mother?”

Both mothers and fathers alike react to the death of a child in many ways, including mourning to the point where they lose their jobs, isolate themselves from their families, and neglect their personal friendships. In the case of Abigail Salmon, her mourning takes the form of introspective and isolation. Instead of leaning into her parental responsibilities or duties to her remaining children, she instead pushes them away and decides to leave the family entirely. She goes to the ocean, and while she is there, she lives only for herself.

The story concludes with Abigail returning to the Salmon family home and resuming her relationship with Jack, although she does not appear to be interested in resuming her motherly duties to Lindsey and Buck. Instead, she simply exists to them as a woman they once called “Mom.” In fact, neither Lindsey nor Buck call Abigail “mom,” nor do they think of her as a maternal figure. She has shed that title. While Abigail now simply views herself as a “woman” and not as a “parent,” she is no happier than she was as Susie’s mom, which leaves readers with yet another question: “What was so bad about being a mother?”

Perhaps what Abigail truly wanted was not to lose her title of “mother,” but to be seen as something more than a parent. Unfortunately, Abigail could not figure out a way to find her own peace while holding onto that title. By the end of the novel, Abigail has effectively shed the label of “mom,” solidifying her figurative death.

For readers, the reality is that Susie isn’t the only one who died on December 6th, 1973. When she was killed by George Harvey, her mother died, too, leaving behind the remnants of a woman who was once known as Abigail Salmon.

Works Cited

Cammaroto, Laura J. “Unexpected: Identity Transformation of Postpartum Women.” James Madison University, Dec. 2009, commons.lib.jmu.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1043&context=edspec201019.

Dow, Dawn Marie. “Integrated Motherhood: Beyond Hegemonic Ideologies of Motherhood.” Journal of Marriage and Family, vol. 78, no. 1, Feb. 2016, pp.180-196. Wiley Online Library, doi.org/10.1111/jomf.12264. Accessed 20 Oct. 2023.

Roche, Rosa et al. “Parent and child perceptions of the child’s health at 2, 4, 6, and 13 months after sibling intensive care or emergency department death.” Journal of the American Association of Nurse Practitioners vol. 33,10 793-801. 21 May. 2020, doi:10.1097/JXX.0000000000000429

Sebold, Alice. The Lovely Bones. Little, Brown and Company, 2002.

— Beth Jones (MA ’25)

3 thoughts on “What Happens to Childless Mothers?”